Lamoureux

Lamoureux

LAC

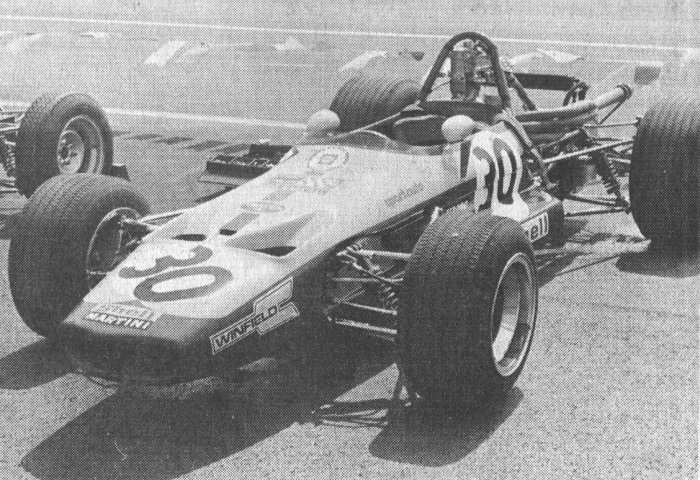

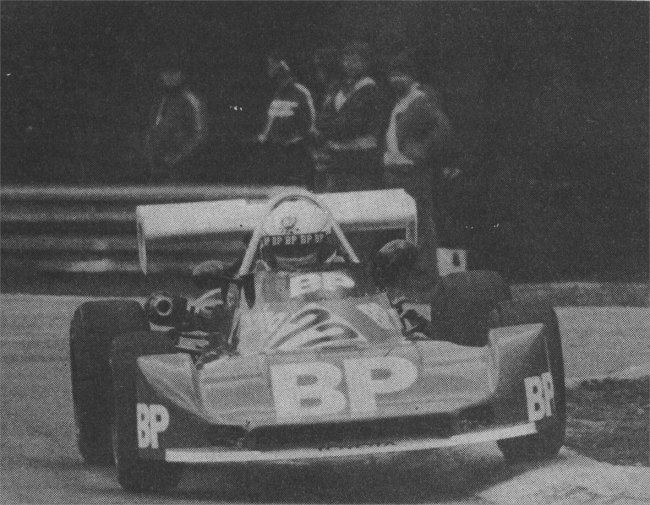

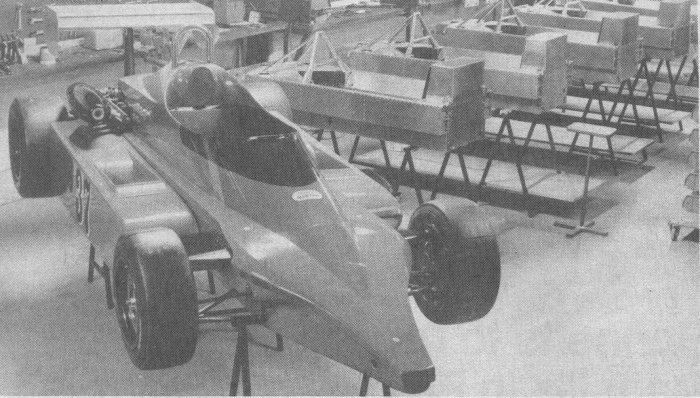

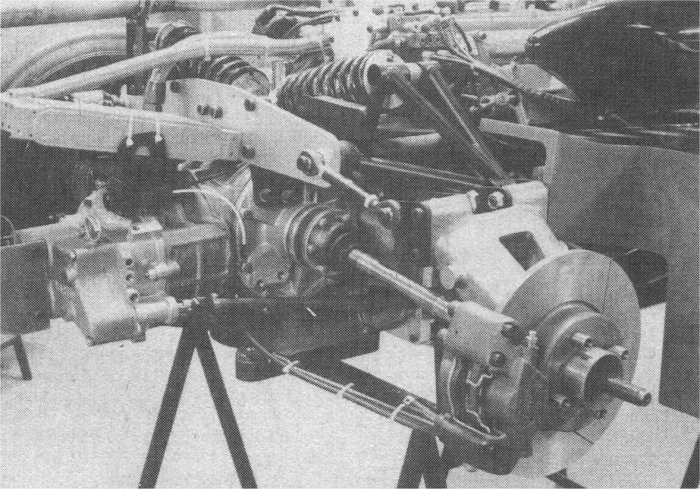

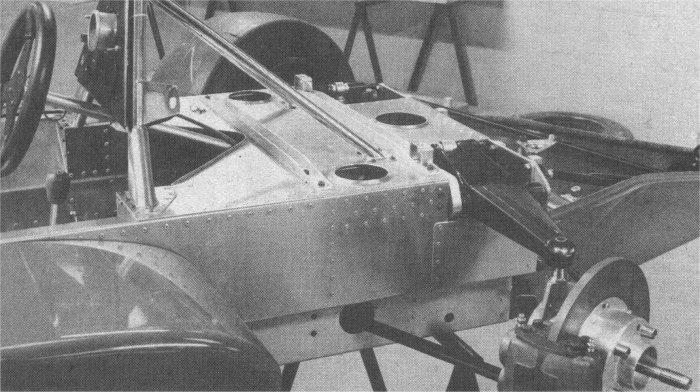

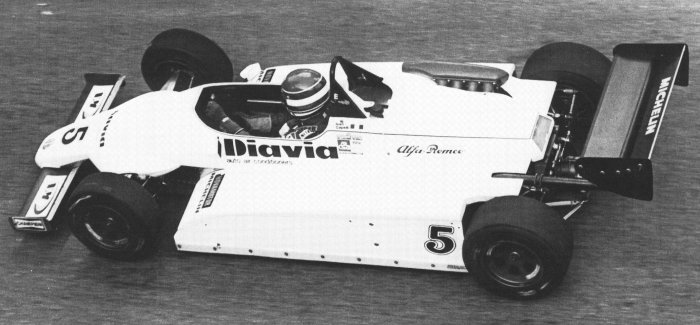

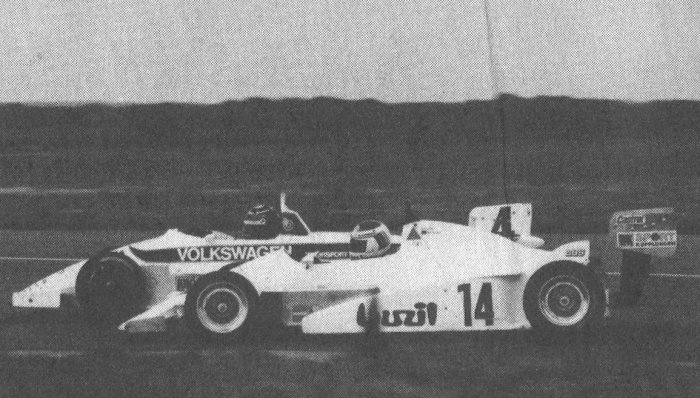

Martini

Martini

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1994

1996

1997

1997

1999

2000

Drivers

1968 MW3

Etienne Vigoreux.

1969

MW4

Jacques Lafitte.

MW3

Jacques Lafitte.

1970

MW5

Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, Jean-Luc Salomon.

MW3

Jimmy Mieusset.

1971 MW7

Phillip Albera, Joel Auvray, Patrice Compain, Jacques Coulon, Guy Dhotel, José Dolhem, Lucien Guitteny, François Laccarrau, François Migault, Marcel Morel, Patrick Perrier, François Rabbione.

1972

MK9

Phillipe Albera, Joel Auvray, Bernard Beguin, John Bisignano, Ray Caruthers, Miguel Coarasa, Jacques Coulon, Guy Dhotel, José Dolhem, Cliff Haworth, François Laccarrau, Philippe Munier.

MW7

José Dolhem, François Rabbione.

1973

MK12

Bernard Beguin, Patryck Boutin, Bernard Chevanne, Alain Cudini, Christian Ethuin, Jacques Laffite, Jean Max, Jean-Pierre Paoli.

MK11

Bernard Beguin, Cliff Haworth.

MK9

Philippe Albera, Patric Boutin, Philippe Munier, Jean Ragnotti.

?

Georges Ansermoz

1974 MK9

Reinhard Pfändler, Marcel Wettstein.

1975 MK9

Reinhard Pfändler.

1976 MK9

Marcel Wettstein.

1977 MK21

Didier Pironi, Danny Snobeck.

1978

MK21B

Patrick Bardinon, Anders Olofsson, Alain Prost.

MK21

Patrick Bardinon, Jacques Coulon, Anders Olofsson.

1979

MK27

Richard Dallest, Jo Gartner, Mats Paninder, Alain Prost, Serge Saulnier, Philippe Streiff.

MK21

Jean-Pierre Malcher, Serge Saulnier.

1980

MK31

Daniele Albertin, Philippe Alliot, Mauro Baldi, Thierry Boutsen, Enzo Coloni, Pascal Fabre, Alain Hubert, Patrick Lancelot, Oscar Ruben Larrauri, Piero Necchi, Vinicio Salmi, Philippe Streiff, Manuel Valls.

MK27/31

Alain Ferté.

MK27

Alfredo Ruggeri.

1981

MK34

Philippe Alliot, Paolo Barilla, Eddy Bianchi, Gerhard Berger, Pascal Fabre, Alain Ferté, Ricardo Galiano, Paolo Giangrossi, Denis Morin, Jean-Michel Neyrial, Emanuele Pirro, Vinicio Salmi, Jean-Louis Schlesser, Philippe Streiff, Patrick Teillet, Didier Theys, Andy Wietzke.

MK31

Jakob Bordoli, Albert Coll, Josef Kaufmann, Michel Lateste, Jean-Michel Neyrial, Pierre Petit, Emanuele Pirro, Riccardo Galiano Ramos, Dominique Tiercellin, Alexandre Yvon, Jean-François Yvon.

MK27

Dieter Bergermann.

?

Manfred Hebben.

1982

MK37

Philippe Alliot, Gerhard Berger, Alain Ferté, Michel Ferté, Franco Forini, Patrick Gonin, François Hesnault, Philippe Huart, Guy Leon-Dufour, Pascal Pessiot, Philippe Renault, Franco Scapini, Alfredo Sebastiani, Patrick Teillet, Didier Theys, Jürg-Pascal Vogt, Walter Voulaz.

MK34

Guido Dacco, Jacques Gambier, Philippe Huart, Josef Kaufmann, Arie Luyendijk, Bernard Santal.

MK31

Jakob Bordoli, Bernard Bribes, Alain Fell, Eric Lukes, Alexandre Neefs, Camilo Parizot, Claude Tourand.

MK21B

Hervé Delaunay.

1983

MK39

Harald Becker, Frédéric Dellavallade, Pascal Fabre, Michel Ferté, Patrick Gonin, Olivier Grouillard, Josef Kaufmann.

MK37

Ferdinand de Lesseps, Pascal Pessiot, Jürg Vogt.

MK35 (Appears to be a converted Super Vee chassis)

Bruno Eichmann, Manfred Hebben, Josef Kaufmann.

MK34

Thomas Bertschinger, Rolf Engert, Cor Euser, Claude Marcq.

MK31

Otto Christmann, Erich Höhmann, Alexander Seibold.

?

Georges A. Hedinger

1984

MK42

Harald Becker, Paul Belmondo, Ivan Capelli, Frédéric Dellavallade, Ricardo Galiano, Bruno di Gioa, Olivier Grouillard, Manfred Hebben, Jean-Pierre Hoursourigaray, Josef Kaufmann, Denis Morin, Pierre-Henri Raphanel, Bernard Santal, Richard Weggelaar.

MK39

Cor Euser, Josef Kaufmann, Jürgen Kühn, Ferdinand de Lesseps.

MK37

Jacky Eeckelaert, Ruedi Schurter.

MK34

Karl-Heinz Wenig.

MK31

Otto Christmann, Erich Höhmann.

1985

MK45

Alex Caffi, Yannick Dalmas, Frédéric Dellavallade, Bruno di Gioia, Philippe de Henning, Franz Konrad, Jean-Noel Lanctuit, Nicola Larini, Gilles Lempereur, Denis Moran, Stefan Neuberger, Jari Nurminen, Markus Oestreich, Pierre-Henri Raphanel, Philippe Renault, Jo Ris, Bartl Stadler, Alfonso de Vinuesa, Volker Weidler.

MK44

Mario Bauer, Helmut Mundas, Rudi Seher, Pietro Spazolla, Alfonso Toledano.

MK42

Bernard Cognet, Franz Hunkeler.

MK39

Bernard Cognet, Karl-Heinz Wenig.

MK35 (Appears to be a converted Super Vee chassis)

Otto Christmann.

MK31

Eberhard Ernst.

1986

MK49

Eric Bachelart, Eric Bellefroid, Eric Bernard, Yannick Dalmas, Markus Oestreich, Manuel Reuter, Michel Trollé, Volker Weidler, Yuuji Yamamoto.

MK45

Gianni Bianchi, Jakob Bordoli, Andy Bovensiepen, Peter Elgaard, Pierre Hirschi, Peter Kroeber, Helmut Mundas, Stefan Neuberger, Franz-Josef Prangemeier, Otto Rensing, Ralf Rauh.

MK44

Willi Bergmeister, Sigi Betz, Helmut Bross, Eberhard Ernst, Richard Hamann, Christian Vogler.

MK37

Romeo Nüssli.

MK35 (Appears to be a converted Super Vee chassis)

Otto Christmann.

MK27

Karl-Heinz Maurer.

?

Adi Lechner, Delia Stegemann.

1987

MK52

Jean Alesi, Markus Oestreich, Otto Rensing.

MK49/52

Jean Alesi, Yuuji Yamamoto.

MK49

Roland Franzen

MK45

Jakob Bordoli, Stefan Neuberger, Bernard Thuner.

MK42

Georg Arbinger.

MK35 (Appears to be a converted Super Vee chassis)

Otto Christmann.

MK31

Karl-Heinz Kerschensteiner.

MK27

Karl-Heinz Maurer.

1988

MK55

Georg Arbinger, Didier Arztet, Frank Biela, Franz Binder, Ellen Lohr, Lionel Robert, Peter Zakowski.

MK52

Frank Biela, Jakob Bordoli.

MK49

Roland Franzen, Georg Neyer.

MK35 (Appears to be a converted Super Vee chassis)

Otto Christmann.

1989

MK58

Cathy Muller, Yvan Muller, Michael Roppes.

MK55

Lionel Robert, Peter Schär.

MK49

Pierre-André Cossy.

MK45

Romeo Nüssli.

1990

MK60

Frank Beyerlein, Franz Engstler, Meik Wagner.

MK58

Olivier Caekebeeke, Walter Kupferschmid.

MK55

Günter Muskovits.

MK52

Romeo Nüssli.

MK49

Richard Neurauter.

?

Roland Bossy.

1991

MK58

Peter Fischer.

MK52

Romeo Nüssli.

?

Walter Kupferschmid.

1992

MK60

Peter Fischer.

MK58

Hansruedi Debrunner.

MK52

Romeo Nüssli.

1993

MK60

Peter Fischer.

MK52

Romeo Nüssli.

1994

MK67

David Dussau.

MK58

Hansruedi Debrunner, Christoph Grossenbacher.

1995 MK45

Othmar Oswald.

1996

MK73

Wolf Henzler.

MK58

André Gauch.

1997

MK73

Tom Coronel, Wolf Henzler, Franck Montagny, Tom Schwister, Oriol Servia, Steffen Widmann, Jaroslaw Wierczuk.

MK58

André Gauch.

1998 MK73

Sebastien Bourdais, Jonathan Cochet, Tomas Enge, Marcel Fassler, Yasutaka Gomi, Wolf Henzler, Thomas Jäger, Pierre Kaffer, Franck Montagny, Timo Rumpfkeil, Toby Scheckter, Timo Schneider, Tom Schwister, Steffen Widmann.

1999 MK79

James Andanson, Westly Barber, Sebastien Bourdais, Marcel Costa, Patrick Frieschar, Ryo Fukuda, Hugo van der Ham, Alexander Müller, Timo Rumpfkeil, Yannick Schroeder.

2000

MK80

Thomas Mutsch.

MK79

Marcos Ambrose, James Andanson, Romain Dumas, Andreas Feichtner, Patrick Hildenbrandt, Ying-Kin Lee, Thomas Mutsch.

MK73

Philip Giebler, Adam Jones.

2001 MK79

Simon Abadie, Jerome dalla Lana.

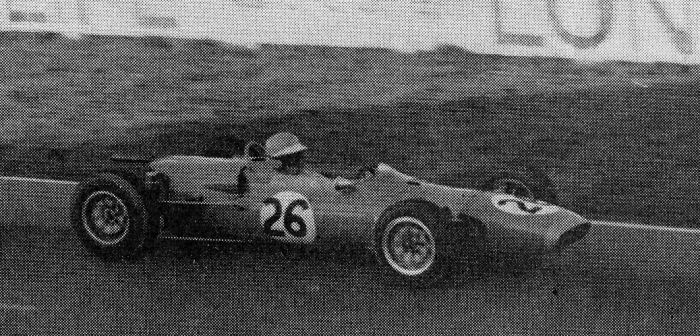

Matra

Matra

1965

1966

1967

1968

Drivers

1965

MS1

Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud.

MS2

Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, Eric Offenstadt.

1966

MS5

Jean-Pierre Beltoise, John Fenning, Jacky Ickx, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, Derek Kavanagh, Henri Pescarolo, Johnny Servoz-Gavin, Claude Vigreux.

1967

MS6

Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, Henri Pescarolo, Roby Weber.

MS5

Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Alain Boudier, Robert Challoy, Michel Dagorne, “Geki”, Jean-Claude Guenard, Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, Johnny Servoz-Gavin, Philippe Vidal.

MS1

Alain Boudier, Serge Mesnil.

1968

MS5

Hervé Bayard, Max Bonnin, Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Adam Potocki.

?

Gérard Bazin.

1969

MS5

Hervé Bayard, Max Bonnin.

Tui

Tui

1970

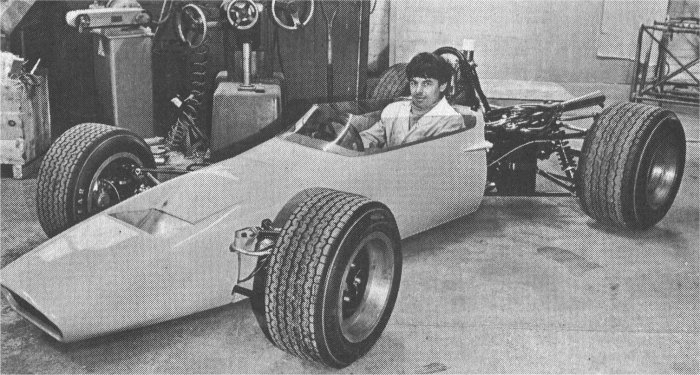

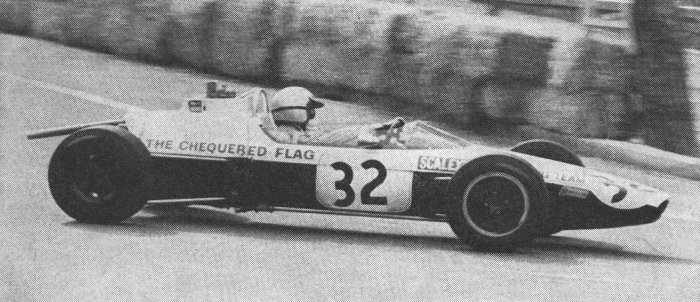

The Tui AM1 consisted of an aluminium monocoque with outboard suspension, the Broadspeed engine acted as a stressed member. Many of the parts used were ex-McLaren including the wheels, uprights and windscreen.

Wheelbase: 84.5 ins.

Track front: 54 ins. Rear: 56 ins.

Bet Hawthorne showed the car had potential but like many of the smaller teams with no budgets getting hold of a decent engine was a problem. The best finish for the AM1 was a fourth in a Lombank round at Brands Hatch.

Drivers:

1970

Bert Hawthorne.

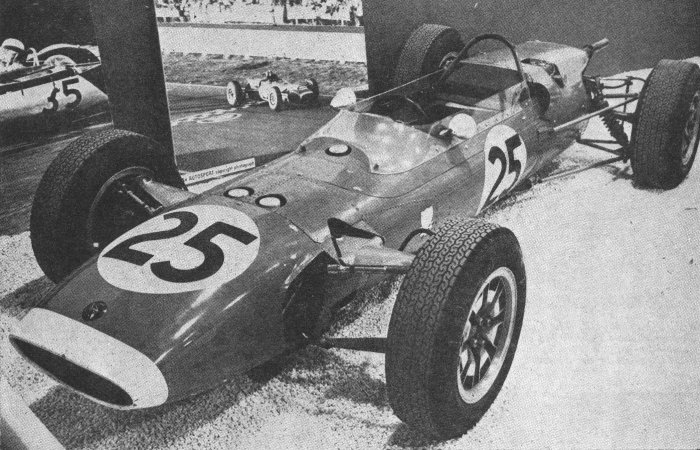

1964

The pictures of the 1964 Abarth F3 indicate that the chassis was the same as that used for the F2 design, in addition track and wheelbase dimensions were virtually identical. It was a conventional spaceframe design with wishbone-based outboard suspension front and rear. Front track was 1320mm, rear 1330mm, wheelbase 2300mm and the chassis weighed 400kg. The engine was a 982cc Fiat-based unit with a four-speed gearbox, a Weber 40DCD carburetor was used and power was quoted as 88bhp at 7900rpm.

For whatever reason, perhaps the F3 engine wasn’t up to the job, the Abarth never raced.

Tom’s

Tom’s

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

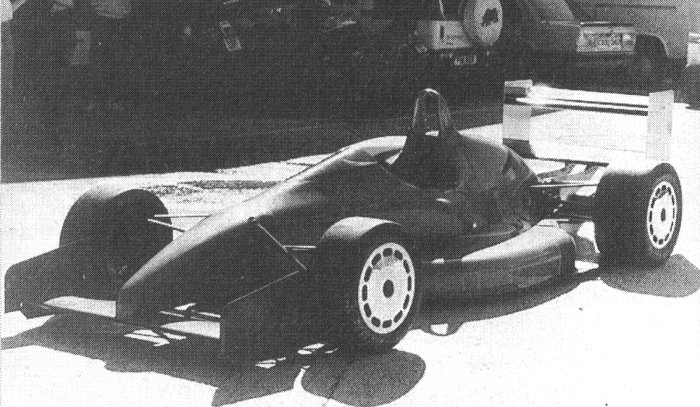

For TOM’S final season as a F3 constructor the 037F was produced. Heavily based on the 036F it featured a modified tub, revised suspension and was fitted with a new gearbox casing. Initially the same aerodynamic package that had been fitted to the 036F was employed. The design revisions were the work of Mark Bailey who was responsible for the Swift F Ford car.

Rather surprisingly TOM’S eschewed the All Japan Championship preferring to run a Dallara for Tom Coronel which in fact was a shrewd move as the won the title. Instead the 037F raced exclusively in the UK, it had problems early on but as the season progressed it showed flashes of promise. Its main weakness seemed to be an inability to get enough heat into its front tyres and it was very inconsistent from circuit to circuit being very quick on one and then slow on another. Kevin McGarrity had the best finish of the year with a third at Oulton Park.

At the end of the year TOM’S ceased building their own cars although they continued in F3 for another year in the UK running Dallaras (and occasionally the 037F). They are still active and successful in Japan, again with Dallaras, in 1998 and ’99 they won the championship.

Drivers:

1991

031F

Paulo Carcasci, Takuya Kurosawa, Victor Rosso, Rickard Rydell.

1992

032F

Naozumi Itou, Tom Kristensen, Victor Rosso, Rickard Rydell, Tetsuya Tanaka, Jacques Villeneuve.

1993

033F

Masahiko Kondou, Tom Kristensen, Hidetoshi Mitsusada, Kazutomo Mizuki, Rickard Rydell, Shinsuke Shibahara, Yoshiyasu Tachi, Toranosuke Takagi, Tetsuya Tanaka, Yoshiro Tani.

032F

Hidetoshi Mitsusada, Yutaka Okano, Shinsuke Shibahara, Yoshio Tsuduki.

1994

034F

Michael Krumm, Toranosuke Takagi.

033F

Michael Graff, Shigeaki Hattori, Yuuji Ide, Russell Ingall, Masami Kageyama, Satoshi Motoyama, Manabu Ootsuka, Hirofumi Sada, Oonishi Taichirou, Toranosuke Takagi, Tsuchiya Takeshi.

031F

Fernando Croceri, Omar Martinez, Ricardo Risatti.

1995

034F

Sebastián Martino, Juan Manuel Silva.

033F

Hiroshi Sasaki, Hidekazu Shigetomi.

031F

Omar Martinez.

1996

036F

Tom Coronel, Syouta Mizuno, Brian Smith, Takashi Yokoyama.

034F

Rubén Derfler, Christian Ledesma, Juan Manuel Silva.

1997

037F

Giovanni Anapoli, Ricardo Mauricio, Kevin McGarrity, Martin O’Connell, Andy Priaulx, Jamie Spence, Darren Turner.

034F

Juan Manuel Silva.

1998 037F

Adam Wilcox.

1999

037F

Gavin Jones.

031F

Javier Catalfo.

McLaren

McLaren

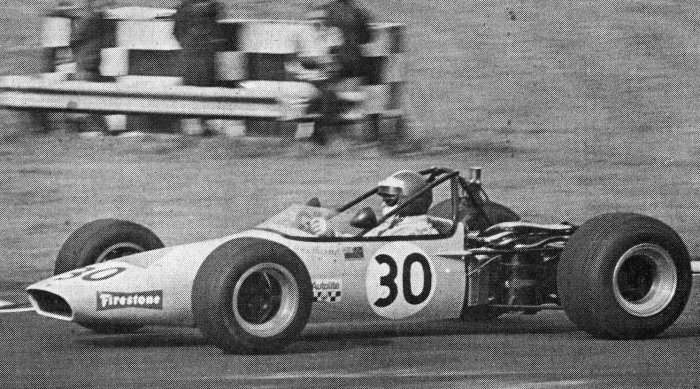

1968

Drivers

1968 Ian Ashley, Mike Walker.

Toj

Toj

1975

1976

1977

For 1977 the F302 was introduced, it used the existing monocoque chassis plan with a conventional outboard suspension layout. Side radiators were fitted and at the front an unusual flat low nose with side wings was attached. During the season both Toyota and BMW engines were fitted and through a combination of good places and reliability Peter Scharmann took the German Championship. Best results were 2nd at the Nurburgring and a 3rd at Diepholz. Perhaps, all things considered, it was best to go out on a high note as this was the last year of ToJ in F3.

Drivers

1975 Not given as the cars still appeared under the Modus name on German F3 entry lists.

1976 Heinz Lange, Keke Rosberg(?).

1977

F302

Peter Scharmann, Walter Spitaler.

F301

Leopold von Bayern, Manfred Cassani.

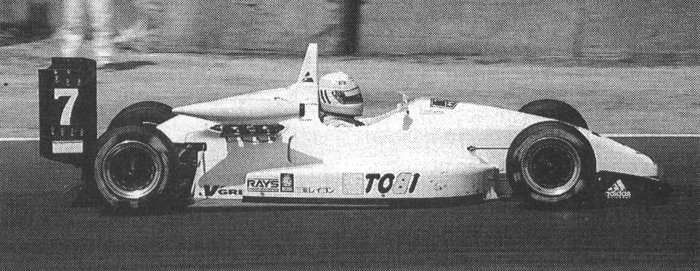

Toda

Toda

Entered by Toda Racing, who also appeared to tune a number of the front-running Toyota engines used in the Japanese championship, the Toyota-powered RS6 took part in four races running at the rear of the field. This seems to have been Toda’s only appearance as a constructor.

Drivers:

1980

Katsuhiko Sugiura.